Toxic Ground

Soil Pollution, City Planning, and Environmental Inequality

Written by Julia Zwerling

Imagine spending years growing fruits and vegetables in your backyard and consuming them for every meal. Then, one day, a soil test reveals that the lead levels in your yard are drastically higher than the government’s safety guidelines. For many residents of Buffalo, New York, this is not a bad dream; it’s a reality. Since it was once a major industrial hub in the late nineteenth century, Buffalo now carries a toxic environmental legacy beneath every front lawn and community garden, even though its local economy has moved away from manufacturing.

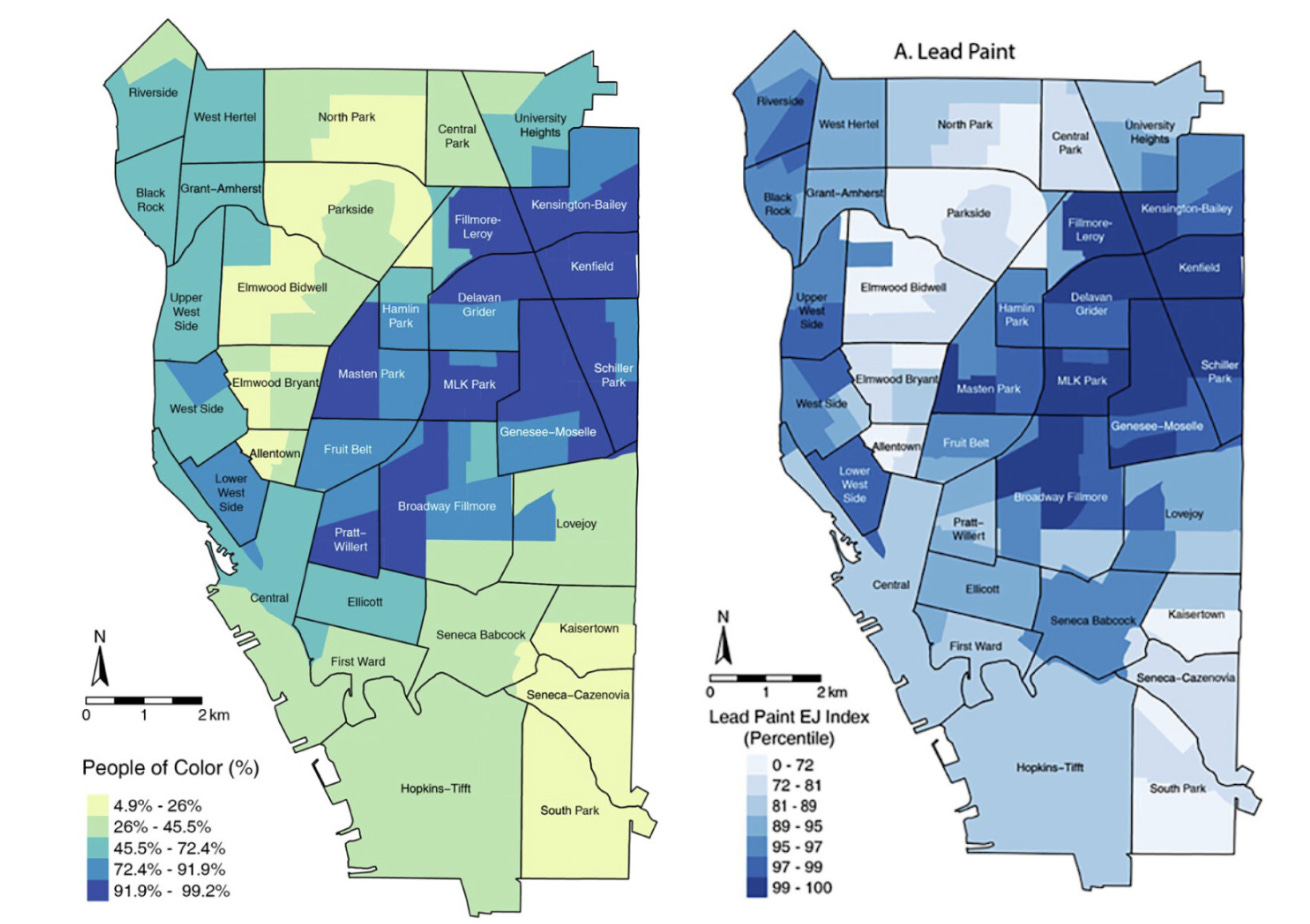

A new study, by researchers at the University at Buffalo, investigates two main questions: How do racial and socioeconomic backgrounds of residents overlap with the levels of chemical contamination in their neighborhoods? And what is the community experience of planning and policy regarding tainted soil? By comparing maps of the spatial distribution of people of color across Buffalo with maps of each neighborhood’s score of lead paint levels and proximity to hazardous waste sites, researchers found that areas with polluted soil were almost always located in predominantly Black, Hispanic, and immigrant neighborhoods.

The study also included focus group interviews of Buffalo residents that centered on their perspectives and experiences with soil contamination. Many participants expressed concern, arguing that tainted soil prevented them from safely growing food in their own backyards. While some completed at-home soil testing kits to stay conscious of their risk, most reported learning about toxicity issues from small neighborhood organizations rather than the government, a point of frustration for people looking for long-term contamination solutions. “This is an infrastructure problem,” commented one interviewee.

Soil contamination is about more than infrastructure; it is about planning. While Buffalo has several zoning policies related to drinking water contamination and lead-based paint, it fails to take action against hazardous soil, and residents are expected to assess these dangers on their own. The study authors call on city leaders in Buffalo and elsewhere to integrate hazardous soil issues into community planning processes, arguing that policymakers should focus on taking direct action rather than relying on local collective organizations to do the heavy lifting.

If you’re interested in reading more about this topic, check out the research led by Alexandra Judelsohn in the Journal of Planning Education and Research.

Judelsohn, A., Frimpong Boamah, E., Adamu, K., Yin, F., Paltseva, A., Kordas, K., Parasnis, M., Chen, T., & Nalam, P. (2025). Envisioning Healthy Soil Futures: Planning and Policy Inertia in Addressing Soil Contamination in a Postindustrial City. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X251373027